Lewis Gordon on how not to read black intellectuals:

The aim of What Fanon Said is to offer a study of Fanon and his ideas in their own right. “What Fanon said,” then, pertains not only to the black letter words in his writings but also to their spirit, their meaning. This task also involves stepping outside of a tendency that often emerges in the study of intellectuals of African descent—namely, the reduction of their thought to the thinkers they study. For example, Jean-Paul Sartre was able to comment on black intellectuals such as Aimé Césaire, Fanon, and Léopold Sédar Senghor without becoming “Césairian,” “Fanonian,” or “Senghorian”; Simone de Beauvoir could comment on the thought of Richard Wright without becoming “Wrightian”; the German sociologist Max Weber could comment on the African American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois without becoming “Du Boisian.” Why, then, is there a different story when black authors comment on their (white) European counterparts? “Standard” scholarship has explored whether Du Bois is Herderian, Hegelian, Marxian, or Weberian; whether Senghor is Heideggerian; and whether Fanon is every one of the Europeans on whom he has commented Adlerian, Bergsonian, Freudian, Hegelian, Husserlian, Lacanian, Marxian,Merleau-Pontian, and Sartrean, to name several.

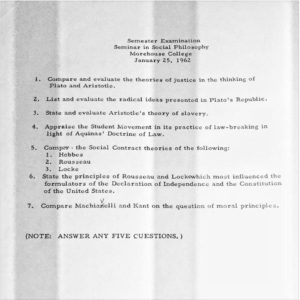

The problem of subordinated theoretical identity is a theme against which Fanon argued. It is connected to another problem—the tendency to reduce black intellectuals to their biographies. Critics of this approach ask: How many biographies of Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Fanon do we need before it is recognized that they also produced ideas? It is as if to say that white thinkers provide theory and black thinkers provide experience for which all seek explanatory force from the former. As there are many studies of Immanuel Kant without reducing him to Jean-Jacques Rousseau (who had the most influence on the former’s moral philosophy), my approach will be to address Fanon’s life and thought as reflections of his own ideals, with the reminder that no thinker produces ideas in a vacuum.

(Lewis R. Gordon, What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and Thought)